Fred Bailey

Sunday, April 1, 2007

Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942. Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942.

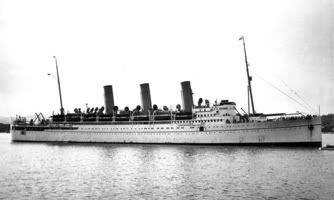

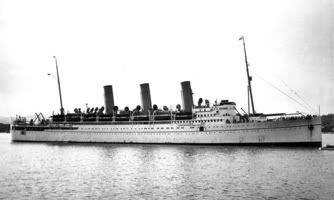

As war began to break-out in the Pacific Region, Fred, along with thousands of other men, volunteered to serve in the British Merchant Navy and was set onboard the Empress of Asia. Built in Glasgow in 1912, the 180 meters long ship weighed 17,000 tonnes and was a passenger liner. But with war raging, the Empress of Asia was converted into an armed troop carrier crewed by the civilian Merchant Navy seamen. Fred Bailey with his wife, May

The Empress of Asia

(image is property of the Empress of Asia Research Group)

By late 1941, The Empress of Asia was sailing for Singapore via Africa, Bombay and across the Indian Ocean, but never made it to the island. On 3rd February 1942, when the cruiser was just 13 miles away from Singapore, it was attacked by the Japanese. The vessel was heavily bombed and subsequently sunk. The crew (Fred Bailey among them) and the ship's military passengers, managed to escape the burning vessel and were eventually rescued by small dinghies or vessels passing by and they were subsequently brought to Singapore. As the men came ashore, they were shocked to see the state of Singapore at the time. "I was driven through Singapore which was a devastation. In the hospital, the dead were mixed up with the living. The wounded weren't treated or fed. There was nobody to cook for them." Leonard Butler

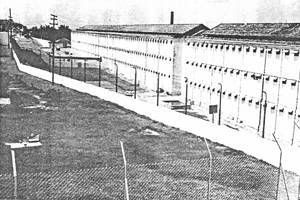

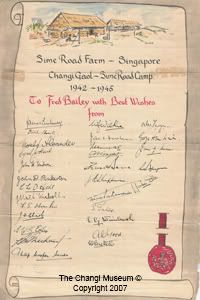

Empress of Asia's youngest survivor In response to the appalling conditions, 147 'Empress' men, including Fred, turned down the offer of a passage home and volunteered to tend to the sick and wounded. Even at the point when the Japanese had taken over Singapore city, Fred and his fellows were still helping to tend to the injured at the Singapore General Hospital. Since the British Merchant Navy crew members were not classifed as military personnel, and not in uniform (unlike Royal Navy sailors), the 'Empress' crewmen were taken as civilian prisoners by the Japanese. Fred was subsequently imprisoned in Changi Gaol as one of the 3,500 civilians, held in a place built to hold only 600 people. During his internment in the prison, Fred had to share a cell with his fellow crew members, Harry Arnold Hesp and William Hughes. The cell that was designed for one prisoner, was to be the Fred's home for the coming years which he had to share with his two new cellmates. Conditions in the prison were harsh because of overcrowding, lack of food, the outbreak of diseases and the brutality of the Japanese sentries. However, Fred never lost his impish sense of humour and after the war, many of his fellow prisoners testified that his capacity for finding laughter even at the bleakest situations played an important role in maintaining spirits and in giving teh captives the strength to endure. Through documents donated to the museum by Fred's nephew, Michael Beddard, Fred was evidently likeable character amongst the other inmates, helping to keep spirits high.

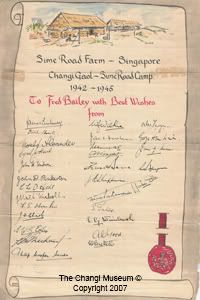

A drawing of scroll and Sime Road Camp with the signatures of several other captives of varying professions. Given to Fred Bailey during his interment. The document serves as evidence of the impact his personality had on his fellow inmates.

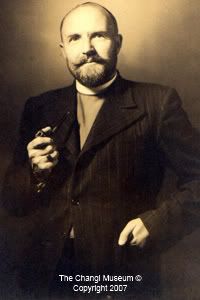

One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix. One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix.

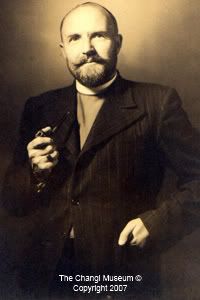

Fred intended to give this cross to his wife, May, as soon as he returned to Britain. However, on the voyage home, he learned that May had passed away from an asthma attack after learning that her husband was safe and returning from Singapore after more than three years of worrying about his fate. Hence upon his return, he was not only burdened with the loss of his wife but was also burdened with the challenge of rekindling his relationship with his two daughters who barely recognised their own father. May's mother, Emily Vernon extended her support to her son-in-law by helping to raise his daughters, Freda and Sheila. In appreciation for her actions, Fred gave the cross to her. Back at home, Fred was still a popular local character in his small town, selling eggs from a basket on his bicycle. The humour and cheer that he carried with him never dwindled, even when he had lost both his legs (as a result of harsh punishments he was compelled to endure whilst in Changi). Reverend Bishop Wilson (above)

Fred Bailey passed away at the age of 78, in 1987. The crucifix (left) that was given to Emily Vernon, was kept safely as one of her most treasured possessions. It was eventually passed down to her grandson Michael Beddard, before she died at the age of 94. The crucifix was donated to the museum in 2005 by Beddard himself and currently resides and is on display at the Changi Museum. "I may never know for sure what the design means but I know what the cross symbolises for me - that the outward differences between people don't really matter: an ordinary working man like Fred and a Prince of the Church like the Bishop, can find themselves in the same circumstances and become friends."

Michael Beddard, nephew of Fred Bailey The museum extends its appreciation to Michael & Pam Beddard, Freda Alcock and Sheila Hewitt for their kind donations and accounting their uncle's/father's history to be preserved in the museum and remembered by the generations to come.

________________________________________________________________

The Palembang Nine

Thursday, March 1, 2007

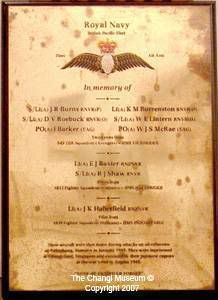

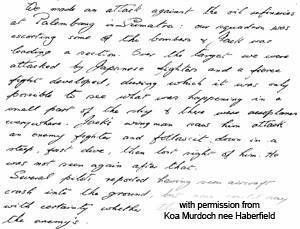

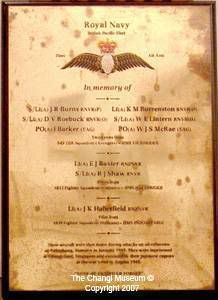

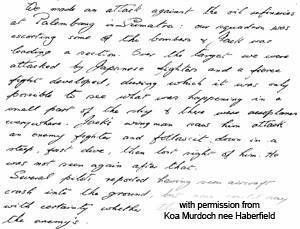

Numerous sabotage missions were launched during the Second World War by Allied forces against the Japanese. Many of these include Operation Krait, Operation Rimau and that on the Japanese cruiser Takao. The British Pacific Fleet, based in Ceylon, had also launched raids over the Nicobars, China Bay Base and parts of Sumatra. The 'Palembang Nine' was a group of nine men from the Royal Navy British Pacific Fleet. The men were either pilots or crew members of the HMS Victorious, the HMS Illustrious or the HMS Indomitable. The 'Palembang Nine' consisted of the following men: Lt. John Haberfield (below)- Pilot from 1839 Fighter Squadron (HMS Indomitable) Lt. Evan John Baxter - Pilot from 1833 Fighter Squadron (HMS Illustrious) S/Lt. Reginald James Shaw - Pilot from 1833 Fighter Squadron (HMS Illustrious) Lt. Kenneth Morgan Burrenston - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) S/Lt. John Robert Burns - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) S/Lt. Donald V Roebuck - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) S/Lt. William Edwin Lintern - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) Petty Officer Ivor Barker - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) Petty Officer J S McRae - Crew from 849 TBR Squadron (HMS Victorious) Information above is based on the Royal Navy British Pacific Fleet Plaque (below), donated to the Changi Museum.  Lieutenant John Haberfield of the HMS Indomitable & The Royal Navy British Pacific Fleet Plaque Lieutenant John Haberfield of the HMS Indomitable & The Royal Navy British Pacific Fleet PlaqueHaberfield, a New Zealander, had enlisted with the Fleet-Air-Arm in August 1941 at the age of 21. He left his home town for service overseas, where he piloted a range of planes, largely orchestrated for carrier-based raids. The last squadron he served was with the 1839 Squadron and the Pacific Fleet, where he piloted Hellcats from the HMS Indomitable. Haberfield had gone missing during his last raid on Palembang, Sumatra on 24th January 1945. The following letter from the Commanding Officer of the 1839 Squadron, addressed to Haberfield's mother, accounts the incidents that led up to his disappearance:  "We made an attack against the oil refineries at Palembang in Sumatra: our squadron was escorting some of the bombers & Jack (Haberfield's nickname) was leading a section. Over the target we were attacked by Japanese fighters and a fierce fight developed, during which it was on possible to see what was happening in a small part of the sky & there were aeroplanes everywhere. Jack's wingman saw him attack an enemy fighter and followed it down in a steep, fast dive, then lost sight of him. He was not seen again after that. Several pilots reported having seen aircraft crash into the ground, but none could say with certainty whether they were our own or the enemy's." "We made an attack against the oil refineries at Palembang in Sumatra: our squadron was escorting some of the bombers & Jack (Haberfield's nickname) was leading a section. Over the target we were attacked by Japanese fighters and a fierce fight developed, during which it was on possible to see what was happening in a small part of the sky & there were aeroplanes everywhere. Jack's wingman saw him attack an enemy fighter and followed it down in a steep, fast dive, then lost sight of him. He was not seen again after that. Several pilots reported having seen aircraft crash into the ground, but none could say with certainty whether they were our own or the enemy's."

Commanding Officer Shotton

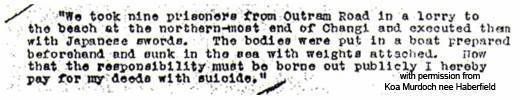

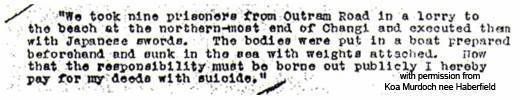

1839 Squadron The oil refineries in Palembang was a critical source of oil for the Japanese, which became the reason why the Fleet had targeted Palembang. Unfortunately the raid was at the expense of the nine men who, like Haberfield, had gone missing. The whereabouts of the nine men had remained unknown throughout the war. It was only after the war ended, that British authorities began to investigate the disappearance of the men in 1946. Investigations began in Palembang; where the men were last seen. It was discovered that the men were kept prisoners in Palembang Prison until February 1945, when they were transferred to Singapore and housed in Outram Gaol. In Singapore, Japanese Major Kataoka Toshio informed British investigating officials that the men had been shipped to Japan for interrogations but never made it as the ships were attacked and sunk by Allied bombings in March 1945. The investigating officer believed that he was telling the truth but it was revealed later by General Atauka, Chief of the Juridical Department for the 7th Army, that the nine men were illegally executed after the war on 15th August 1945. Upon discovering this, investigating officials were prepared to arrest Major Toshio and Captain Okeda (the officials responsible for the men's execution). However before that could have been done, both men committed suicide. The following was written by Major Toshio before he committed suicide:  The museum has been in touch with John Haberfield's sister, Koa Murdoch since June 2002. Murdoch had been generous enough to donate a memorial plaque of her brother to the museum along with several other vital documents, documenting the events leading up to her brother's death.  Koa Murdoch with her late husband in 2002 Koa Murdoch with her late husband in 2002

The identities of the other eight men was never properly investigated.

Recent information suggests that some of the mentioned eight men were not even shipped to Singapore. One of the men was reported to have been seen in Tokyo in April 1945, while some of the other men were reportedly executed shortly after the raids and not executed in Singapore. Hence they were not part of the Palembang Nine.

Also, strong evidence suggests that over 30 Fleet Air-Arm aircrew were executed during captivity, than just the 'Palembang Nine'.

To the museum's knowledge, sufficient documentation is able to conclude that Haberfield was one of the 'Palembang Nine'. However, the identities of the other eight men who were shipped to Singapore with Haberfield, cannot be confirmed due to insufficient and conflicting information.

The Changi Museum extends their thanks to Koa Murdoch for sharing various documents, materials and photographs of her late brother and assisting in preserving the memory of him.

________________________________________________________________

A Man Of Passion ... Misunderstood

Thursday, February 1, 2007

Many stories have been born out of those dark days of Singapore's history that was the Japanese Occupation. Death and torture was everywhere, and it became a struggle for the men and women of those times merely to survive, to keep on a gentle string what little of their lives they still had left.

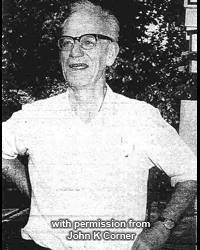

A fine example would be that of Professor Edred John Henry (E.J.H) Corner (1906 - 1996), who was not a military-man, but, in fact, a botanist. In sepia-tinged photographs, he is exactly what you would expect him to be: bespectacled, mild-looking and keen-eyed. Pictures of him with family leave it difficult to imagine that their lives were under the strain of such a cruel war.

John Corner with his wife, Sheila and son, John Kavanagh CornerCorner was born in London in 1906. His interest in Botany began at Rugby School and developed strongly at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. This was before he was appointed as the Assistant Director of the Gardens Department of the Straits Settlements. in 1929. Corner was an expert who who achieved many academic medals and scientific recognition including the Darwin Medal in 1960. He also became well-known for his skill of using Berok monkeys to help him obtain plant specimens that were too high in the canopy to collect. He remained a prominent figure in his field, until the arrival of the Japanese in 1942.

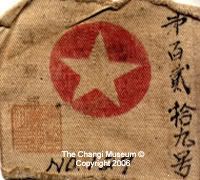

An article on one of Corner's Berok monkeys named Merah. Click here to read article.Corner was drafted as a member of the Singapore Volunteer Force. However, he was unable to fight after receiving a serious bite from one of his monkeys. On the verge of Singapore's fall to the Japanese, the British Governor of Singapore, Sir Shenton Thomas, scribbled a note addressed to the new Japanese commander, recommending that Corner along with Professor Eric Holttum (director of the Botanical Gardens) and William Birtwhistle (Director of Fisheries) should be allowed to continue their work in the gardens to preserve the island's plant-life. Birtwhistle was conversant in the Japanese language after visiting Japan several years before Singapore's fall. Being familiar with the Japanese culture, he was well-respected by the Japanese. It was due to this that he was selected by Sir Shenton Thomas to preserve the Botanical Gardens along with Corner and Holttum. The Japanese Emperor Hirohito, being an orchid enthusiast himself, gave direct orders to allow these men to continue their work with the Japanese. Also, Corner strongly believed that when it came to Science, any prejudice against any scientist of a different nationality or race, was unjustified. He believed that scientists had to be judged for their scientific work and research. Hence, upon the fall of Singapore, the men followed orders and continued their scientific work in the Botanical Gardens and were labelled as 'enemy aliens' by the Japanese and like other 'enemy aliens' they were required to wear a red star.

John Corner and William Birtwhistle, seen here, each wearing a patch with the red star on their shirts. The red star was worn by enemies of the Japanese who

were allowed to live outside prisons or camps.With the assistance of Professor Hidezo Tanakadate and Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa, the men had successfully protected thousands of scientific specimens and hundreds of collections from the museums and libraries during a time chaotic with looting and destruction. Their close working relationship with the Japanese however, resulted in many calling them a collaborator with the enemy. This was despite the fact that Corner himself had even organised food rations and supplies during the trying time of the Japanese Occupation. Many did not know that Corner had been smuggling food into prison camps for them. The three men were however commended in the November 1945 General Report to the British Colonial Office - "The action of these officers in remaining at their scientific posts despite the adverse view of this which inevitably arose among those who were interned, has had results of the utmost value and scientific importance, and is to be highly commended." Source: British National Archives

Reference No: CO 273/675/6 His controversial image continued after the end of the war and long after he had left Singapore in November 1945. Following his departure, he became Principal Field Scientific Officer for Latin America for UNESCO from 1947 to 1948, before returning to Cambridge and becoming Professor of Tropical Botany. He continued to lecture at Cambridge until 1973, when he retired as Emeritus Professor. In 1981, Professor Corner charted his wartime experiences in the book, 'The Marquis: a tale of Syonan-to’. In this book, he mentioned a note from Sir Shenton Thomas, that had given him approval to help preserve the Botanic Gardens and Raffles Museum. According to him, this note was lost in a fire in 1945 in Sendai, Japan, however, which only kept matters ambiguous. The book was shied away from by British publishers, and was only published by Heinemann (Asia). Professor Corner’s other works include several scientific books and papers, as well as a scientific obituary of the Emperor Hirohito written for the Royal Society. It was only in 2000 that evidence was found that the destroyed note had been published in a Japanese newspaper in 1942, the Asahi Shimbun by Professor Tanakadate. Corner was a man of high principle who devoted his life to Botany. In his writings he changed the face of much that had gone before and the evidence now is overwhelming that he never collaborated with the Japanese but rather he gave sufficient co-operation to ensure the safety of all the vital scientific records. As an enemy alien he was also able to help many prisoners, but entirely anonymously and at great risk to himself. He was a self-effacing man who shunned that kind of recognition. His scientific work was everything to him.

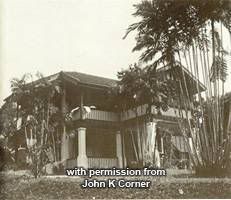

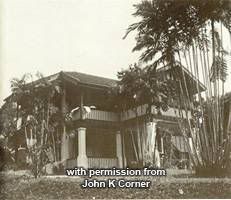

John Corner at the age of 66. Photograph taken by Ismail bin Ahmad.To date, opinions of Professor Corner remain divided. Some maintain their distrustful image of him despite evidence of his innocence, while others, notably students, remember him fondly for his teaching and the stories he had to tell and they see him as a hero who held his own and was true to himself. Corner's colonial bungalow on Cluny Road, now within the Singapore Botanical Gardens, has been converted into a restaurant and is fondly remembered as the "E.J.H Corner House".

John Corner's colonial bungalow house at 30 Cluny Road.

Now a restaurant in the Singapore Botanic Gardens.Professor Corner had unfortunately passed away before he got this chance to clear his name. He died in 1996 at the age of 90. He married twice in his lifetime, and is succeeded today by a son and daughter.  The museum extends their appreciation to his son, John Kavanagh Corner for sharing the story of his father, Professor Corner, and donating articles and photographs of him to the museum. The family photograph above was taken in 2003. From left: John K Corner's children, Andrew Corner and Katie Buckley, Corner's wife, Belinda, John K Corner and Belinda's cousin. John K Corner can be contacted at astley22@bigpond.net.au for further information and the full 1945 General Report. Drafted by volunteer writer Lyana Shah.

________________________________________________________________

Selarang Barracks Square Incident

Monday, January 1, 2007

Selarang Camp, now the headquarters of Singapore's 9th Infantry Division, was once the congested dwelling grounds of 15 000 Australian Prisoners of War (POWs) during the Japanese Occupation in Singapore early 1942. It was one of the many sites in Singapore where prisoners were housed and kept under confinement.

Aerial view of Selarang Barracks 1953 - 1955 Aerial view of Selarang Barracks 1953 - 1955

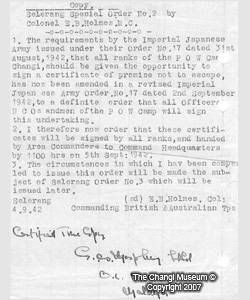

RAF Changi Association Ref No. MI/0198Built in 1938, Selarang Barracks, as it was first known as, was used to house a battalion of the Gordon Highlanders until the war broke out in Singapore in 1942. In August 1942, an incident involving 4 escapees, sparked the infamous Selarang Barracks Square Incident. The four escapees, Pte Rodney Breavington, Pte Victor Gale, Pte Harold Waters and Pte Eric Fletcher, had earlier attempted to escape from Singapore however, they were eventually caught by the Japanese and were returned to Changi, awaiting punishment. Afraid that several other POWs would follow suit, the Japanese had instructed all POWs to sign a no-escape agreement. Unsurprisingly, the POWs refused to sign the agreement. In an attempt to force the prisoners to sign the no-escape agreement, the Japanese had forced all of the prisoners into the parade square of Selarang Barracks leaving them in crowded and unsheltered conditions. The parade square was only one square kilometer large and was equipped with just two working taps. The area was only meant to hold 1200 people, however over 15000 Australian and British POWs were cramped there.

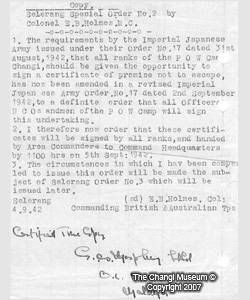

A scene from the Selarang Barracks Square Incident in September 1942. The photograph was secretly taken by George Aspinall.Conditions worsened throughout the days the men were confined into that small area. Toilets were beginning to overflow and dysentery was beginning to spread rapidly. Eventually the Japanese became very angry by this blatant and massive act of defiance, and threatened to move all of the sick men from all the hospitals, into the area. This eventually compelled senior officers to instruct their men to sign the no-escape agreement. The quotation below, donated by Charles Schofield, is an extract of a document from a senior officer, instructing all men to sign the agreement.  "I ... now order that these certificates will be signed by all ranks and handed by Area Commanders to Command headquarters by 1100 hrs on 5th Sept: 1942 . The circumstances in which I have been compelled to issue this order will be made the subject of the Selerang Order No.3 which will be issued later. "I ... now order that these certificates will be signed by all ranks and handed by Area Commanders to Command headquarters by 1100 hrs on 5th Sept: 1942 . The circumstances in which I have been compelled to issue this order will be made the subject of the Selerang Order No.3 which will be issued later.

Selerang 4.9.42 (sd)

E.B.Holmes. Col: Commanding British & Australian Tps"

As a result, the prisoners gave in to the Japanese prison commanders and signed the document. However, unknown to the Japanese, the men were signing fictitious names:

"We all signed fictitious names. The Japs never knew. I mean, I signed 'Winston Churchill'. Some put down 'Mickey Mouse' and some put 'Charlie Chaplin' and others, whatever."

Charles Lyons

British POW

The four escapees who had been captured by the Japanese earlier, were executed shortly after they sparked the Selarang Barracks Square Incident. On 2nd September 1942, the four men were executed in front of their senior officers at Selarang Beach. Before their execution, the men had their names read out by a translator and were told they were to be executed for attempting to escape. They were given five minutes to prepare themselves. One of the men, Rodney Breavington, had stepped forward and pleaded to the Japanese to spare Pte Gale's life, telling them that Gale had only escaped upon Breavington's orders. His pleas were dismissed and all four men were executed and they were buried in shallow graves at Selarang Beach.

Rodney Breavington with his wife (left) and Victor Gale (right)Breavington's act of heroism had inspired the following poem to be written by an anonymous person:

Corporal and his Pal

He stood, a dauntless figure

Prepared to meet his fate.

Upon his lips a kindly smile,

One arm around his mate.

His free hand held a picture

Of the one he hold most dear,

And though the hand was trembling

It was not caused by fear.

No braver man e’er faced his death

Before a firing squad

Than stood that day upon the square

And placed his trust in God.

He drew himself up proudly

And faced his leering foe.

His rugged face grew stern: “I ask

One favour ere I go.

Grant unto me this last request

That’s in your power to give,

For myself I ask no mercy

But let my comrade live.”

Then turning to the guardhouse

Where his sad-faced Colonel stands

A witness to his pending fate

He stiffened to attention

His hand swings up on high

To hat brim, in a swift salute

“I’m ready now to die”.

They murdered him in hatred

And prolonged his tortured end

In spite of all his pleadings

They turned and shot his friend.

They said he was example

Of what they had in store

For others who attempt escape

Whilst Prisoners-of-War

Examples, yes ~ of how to die

And how to meet one’s fate,

Example, true ~ of selfless love

A man has for his mate.

And when he reaches Heaven’s gate

Then Angels will be nigh

And welcome to their midst a man

Who knew the way to die.

Whilst here below in letters gold,

The scroll of fame e’er shall

The story tell of how they died,

A Corporal and his Pal.

________________________________________________________________

"I Will Walk Out On My Own Two Feet"

Friday, December 1, 2006

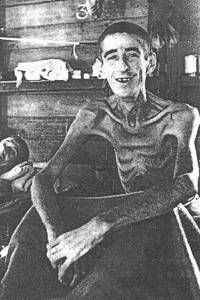

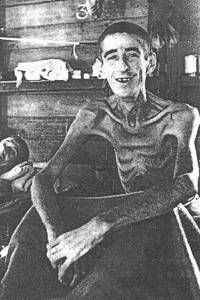

Just one photograph saddened, shocked but inspired the world. A man smiling into the lens of a camera, though sick and reduced to a skeletal frame, displayed an indomitable spirit that touched the hearts of many. His name was John ‘Jack’ Sharpe.

Just one photograph saddened, shocked but inspired the world. A man smiling into the lens of a camera, though sick and reduced to a skeletal frame, displayed an indomitable spirit that touched the hearts of many. His name was John ‘Jack’ Sharpe.

The renowned photograph of POW, Jack Sharpe, The renowned photograph of POW, Jack Sharpe,

smiling, despite being reduced to bones.Jack Sharpe was serving with the 2nd Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment. He trained in Britain before being sent to India. He was eventually sent to Singapore just a few days before the invasion of Singapore. He was captured by the Japanese during the fall of Singapore in 1942.  Jack Sharpe in his uniform (pre-war) Jack Sharpe in his uniform (pre-war)He was first interned in Changi before being sent to Ban Pong, Thailand to work as a slave labourer on the Thai-Burma railway. Whilst in camp, he noticed that the Japanese guards had not been particularly attentive to their duties, believing that no one would escape. He took advantage of the situation and escaped from his camp, however he was eventually caught by a Thai local and was handed back over to the Japanese. Upon his return, Sharpe was put in front of a firing squad, expecting his death. He waited for the gun blasts to fire through the air, signaling his end, but fortunately, that was not to be. A Japanese colonel had intervened before the firing and quarreled with the officer in-charge over Sharpe's fate. After an anticipating wait, the colonel walked over to Sharpe repeatedly hit him with a scabbard and kicked him before ordering him to get up. With hands tied, he was marched back to Ban Pong and was handed back to a guard. The Japanese guard who had been a frontline soldier himself had respected Sharpe for his daring escape. He loosened the straps binding his wrists and handed him a cigarette. Jack Sharpe recalled several years later: "I remember it was a Three Castles cigarette. I enjoyed it.

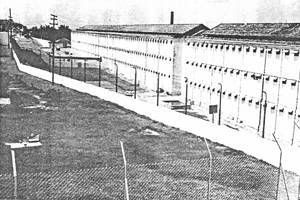

As I finished it, the guard turned to me and said: 'That will be the last cigarette you ever smoke.'"He was sent to a place called the 'house of cages' in Bangkok where he attended a court martial for trying to escape. Initially he was sentenced to two years imprisonment. However, after the president of the court asked him if he had anything to say, Sharpe daringly began to curse the Japanese. Subsequently, his sentence more than doubled. The president of the court was more than furious and insulted Sharpe by saying that no Japanese soldier with a body as strong as his, would allow himself to become prisoner. That was when Sharpe told him off and said that he would live to see all of Japan surrender and that he would walk out of the prison on his own two feet. The insult gave Sharpe the will to live. Sharpe was subsequently brought to Singapore where he faced the infamous Outram Gaol. He knew that no one would be able to survive Outram Gaol two years, much less four and a half years. Few were known to have survived Outram Gaol.  Outram Gaol, courtesy of Outram Gaol, courtesy of

National Archives of Singapore (c.1963)Sharpe was placed in solitary confinement for 14 months. Conditions were poor and long hours of sleep was difficult because the sentry would bang on the door every hour of the night and he would have to call out 'yes' in Japanese. Sometimes they would simply beat up him up when they wanted to find something to do. Sharpe was full of lice and he was fed three meagre bowls of rice a day and a mug of dirty water. He was eventually brought out of solitary confinement and worked during the day with the other prisoners. Death had become part and parcel of Jack Sharpe's life in prison. Many were dying from the physical abuse and beatings by the Japanese. The prisoners had also contracted diseases from contaminated water and died as a result. If prisoners did not die from deterioration of health, they died as a result of execution. As more and more people began to die within the walls of Outram Gaol, the Japanese became concerned about the reputation of the building. Hence they began to transfer some of the prisoners to Changi Gaol which had medical facilities. Sharpe was asked to move to Changi but he refused. Sharpe couldn't help but remember the promise he made to the president of the court, that he would walk out of Outram Gaol on his own two feet. He was determined to fulfill that promise. He contracted scurvy and scabies during his internment which resulted in the deaths of many others but he kept telling himself to go on. His scabs disappeared eventually as he kept his will to live however more and more men around him were either starving to death or they simply gave up. "The only time I faltered was when my best friend - the one who was beaten - died. I couldn't see the sense in going on but I had to."It was in May 1945 that he heard that the war ended in Europe. That gave Sharpe a sense of hope that war would end in the Pacific as well. In August that same year, the Japanese finally surrendered. When the camp was relieved, and he was being carried out of the building, he noticed the sign over the gate. He instructed the men to put him down because he insisted that he had to walk out of the gates on his own two feet. He staggered on his own past the gates of Outram Gaol before being picked up again and sent for treatment at Changi. He was unconscious for 48 hours. When he came around, a non-commission officer gave him 38 letters, all from Sharpe's mother who had written to him every month despite being told that her son was 'missing - presumed dead'. His mother never lost faith. Sharpe was the longest survivor of Outram Gaol. Upon his capture, he weighed 70 kilograms. Upon his release, he weighed less than 25 kilograms. Jack Sharpe returned to England in January 1946 and spent over a year recovering. In an email written to the museum by Jack Sharpe's daughter & son-in-law, Ray & Paul Brotherton: "When he felt able, he visited the next village as a 'trip out'. In that village he visited the local public house where he met and fell in love with a barmaid called Sophia. They married in April 1947. They raised a family of one son John, and a daughter called Ray."  Jack Sharpe with his two children, Ray and John in London (1956) Jack Sharpe with his two children, Ray and John in London (1956) Jack Sharpe getting married to Sophia on April 5th 1947 Jack Sharpe getting married to Sophia on April 5th 1947Sharpe had made another vow to himself after the war ended, that he would outlive the Japanese Emperor (which he did). The impact of the war on his life and on several Prisoners Of War (POWs) had become very apparent during a protest against the Emperor's son's visit to London where many of these ex-POWs, including Sharpe, turned their backs as the cars ferrying the Emperor's son, passed them.

Bill Cobley, Jack Sharpe & Phil Dixon before the

protest against the Emperor's Son's visit to London (May 1998)Despite the brutalities committed against him, Sharpe did not hold a real grudge against the Japanese which showed by the fact that he rode a Japanese-made motorcycle for many years (unlike several POWs who boycotted Japanese-manufactured products). Jack rarely spoke of his experience during the war, to his children. However with time he began to finally tell his grandson, Ian, about his experiences. The legendary photograph of Jack Sharpe hangs in the Imperial War Museum and is also on display at the Changi Museum. Jack Sharpe, though reluctant, summoned his strength to visit the museum on 17th February 2002, during the 60th anniversary of the fall of Singapore.  Jack Sharpe next to his own photograph at the Changi Museum in 2002. Jack Sharpe next to his own photograph at the Changi Museum in 2002.Jack Sharpe became a gardener after the war then retired as a much-loved school caretaker. He peacefully passed on in Leicester, 13th August 2002.  The museum extends their appreciation to the Brotherton family for their contributions to the museum for making Jack Sharpe's story complete. The photograph above was taken during their visit in September 2005. From left: Heather, Ian, Ray & Paul Brotherton. This adapted from http://www.findarticles.com and the article "Death was all around me every day for 3 1/2 years" from an unknown source. Donated by the Brotherton family. The museum extends their appreciation to the Brotherton family for their contributions to the museum for making Jack Sharpe's story complete. The photograph above was taken during their visit in September 2005. From left: Heather, Ian, Ray & Paul Brotherton. This adapted from http://www.findarticles.com and the article "Death was all around me every day for 3 1/2 years" from an unknown source. Donated by the Brotherton family.

________________________________________________________________

A War Heroine - Elizabeth Choy

Wednesday, November 1, 2006

Elizabeth Su Moi Yong, born in 1910, moved from Sabah, North Borneo to Singapore in December 1929. She moved to Singapore in search of higher education, and enrolled into The Convent Of Holy Jesus with her Aunt. She excelled in her studies at the convent, even receiving the most outstanding student award, not just academically but the most outstanding in character as well.

After her Senior Cambridge examination, Elizabeth Yong decided to work instead of pursuing her education further, to provide for her younger siblings. She chose to enter the teaching profession and began doing so at St. Margaret's School for two years before being offered a teaching position at St. Andrew's School.

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, Elizabeth Yong married Choy Khun Heng, who was the oldest son of an old lady who was her classmate's guardian. The old lady took a liking for Ms Yong and asked her to marry her eldest son. 10 years after first meeting with her, she finally tied the knot with Mr Choy on 16th August 1941.

Mr and Mrs Choy on their wedding day After Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15th February 1942, Elizabeth Choy and her husband found themselves without jobs. Subjects in school were no longer in English, hence Mrs. Choy had to stop teaching and the Borneo Co. where Mr. Choy worked at, ceased to exist once the Japanese took over Singapore. However, doctors and nurses who knew the couple, urged them to help run a canteen stall in the Miyako Hospital (also known as the Woodbridge Hospital) to help provide basic essentials to everyone.

They ran the stall together with the primary aim of providing fundamental necessities to the public however it didn't take long before it became a central area for the exchange of messages, medicine and food to the prisoners of Changi.

After the 'Double Tenth' incident (where the Japanese arrested 57 prisoners for possible involvement with a successful sabotage mission that destroyed 6 Japanese oil tankers at Keppel Harbour), Elizabeth Choy and her husband were detained in the Japanese Kempetai (military police) headquarters, the former YMCA building.

The former YMCA building Mr. Choy was detained, on 29th October 1943, for passing radio parts and money to internees in Changi Prison. Worried that she would never see her husband, Mrs. Choy went down to the YMCA building, demanding to see her husband. She was turned away and told to go home. However, on 15 November 1943, a Japanese officer visited her house up at MacKenzie Road, asking her if she wanted to see her husband. She agreed and followed the Japanese office to the YMCA building. There, her valuables were confiscated and she was led to a dark cell with about another 20 prisoners.

The three by four metres cell was to be her home with the other prisoners, for the next 193 days.

Mrs. Choy, along with the other 20 or so male prisoners, had to live in those squalid conditions with very little food, ventilation and clean water. They were also not allowed to talk or move from their cross-legged seating position. Although they were not allowed to speak, the prisoners continued to communicate with each other through the use of sign language which was taught by one of the fellow prisoners.

Mrs. Choy had been brutally treated during her internment. She was subjected to beatings by the Japanese officers and was even electrocuted in front of her husband. The Japanese tried to force her into giving out the names of informants or admitting that she was anti-Japanese. After 193 days, the Japanese finally released her from prison, after learning that they would never get the 'confession' that they wanted out of her. She was released the day after her husband was sentenced to 12 years of rigorous imprisonment on 25th May 1944.

After the war ended on 12 September 1945, she traced her husband's whereabouts to Outram Gaol and together with a British soldier, they freed him. Although he regained his freedom, Choy Khun Heng never fully regained his health.

After her ordeal, Mrs. Choy developed a fear of electricity and electrical appliances. She would even avoid turning on a simple switch at all costs. Despite having this lifelong fear as a result of the atrocities inflicted upon her during the war, when given the opportunity to identify the Japanese officer that tortured her, to be sentenced at the War Crimes Tribunal, she refused to provide any names stating that she condemned war and not the people who tortured her.

After the war, the Red Cross had offered the Choys to live in Britain since their house was in ruins and was heavily looted during the war. Only Mrs. Choy accepted the offer and she flew to Britain in 1946.

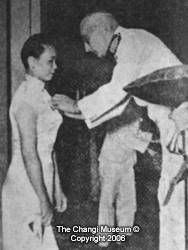

That same year, she and her husband were awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for their efforts during the war. She only returned to Singapore just before Christmas Eve in 1949. It was only after her return that she received the medal at an official ceremony.

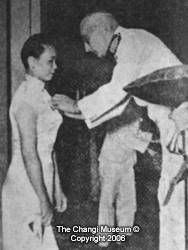

Elizabeth Choy receiving the OBE from Governor Sir Patrick McKerron. Upon her return, she contested in the Municipal Council Elections and became the first woman to be nominated as a member of the Legislative Council. She eventually retired from politics in 1955.

The following year she helped set up the School for the Blind and served as the principal of the school. Elizabeth Choy, together with Mr. Ron Chandran-Dudley, secretary of the Disabled People's Association, made visits to the villages to convince skeptical parents of blind children to allow them to go to school. She retired from teaching in 1974.

By the time of her retirement, she had been awarded several medals not just for her bravery but also for her contribution to society. On top of the OBE, she also received the Order of the Star of Sarawak (OSS) from the Raja of Sarawak.

She received this in appreciation of her pre-war work as a volunteer nurse, where she helped many Sarawakians. The Bronze Cross (BC) from the Girl Guide movement in England (the movement's highest award), was also awarded to Mrs. Choy in recognition for her valour during the Japanese occupation. And lastly she received the Pingkat Bakti Setia (PBS) or the Long Service Teaching Award from Singapore.

Elizabeth Choy with her medals Her efforts during the war was remembered and documented on several occasions. Firstly, a TheatreWorks production entitled, Not Afraid To Remember was staged in 1986. The director, Lim Siauw Chong, was a student in St. Andrew's where Elizabeth Choy taught. He only found out about her war experiences, while doing research, several years later. He subsequently pushed for the staging of the production.

Secondly, a biography of Elizabeth Choy was released in 1995, written by Zhou Mei, entitled Elizabeth Choy - More Than A War Heroine. This followed by an exhibition two years later, by the National Museum entitled, Elizabeth Choy - A Woman Ahead of Her Time.

Elizabeth Choy - More Than A War Heroine. A biography by Zhou Mei. Elizabeth Choy was unfortunately diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2006 and peacefully passed away on 14th of September 2006 at her MacKenzie Road home. Her wake was held at the St. Andrew's Cathedral. It was the first time in St. Andrew's 150-year history that the a wake was allowed to be held to be held on the Cathedral premises. Considering her contributions to the school, society and country, they made an exception for the war heroine. She is also fondly remembered by the Changi Museum as a war heroine and as a friend.

Elizabeth Choy with her grand-daughter at the Changi Museum on 30th September 2003 The Changi Museum extends their heartfelt condolences to the Choy family.

________________________________________________________________

Love Through War - Stanley Durston & Pat Bracken

Sunday, October 1, 2006

It was a casual evening at the Great World club in Singapore 1941 that sealed the fate between Stanley Durston and Pat Bracken. Stanley had met the young lady for the first time at that club, after being introduced by Pat's godmother who had earlier on met him in Port Dickson. For Stanley, it was love at first sight and he knew that he wanted to spend the rest of his life with her.

Stanley Durston and Pat Bracken

Stanley, who was of Welsh descent, grew up in Cumaman, South Wales with six other brothers and sisters. He led a difficult life especially after his father passed away in 1926; when Stanley was only 7 years of age. Despite the financial hardships that his family went through, he had led an overall uncomplicated life. Stanley had a thirst for adventure and knowledge which was why he willingly signed up for the Royal Horse Artillery when he turned 17. Eventually news got out that the Army was looking for volunteers to serve in Singapore. Attracted by the mysteries of a foreign land, he, together with his close friend Doug, signed up and set sail to Singapore. In Singapore, both of them were instantly dispatched to the 9th Regiment - 7th Coastal Battery 15 inch coastal defence guns.

Group shot used as propaganda for the 15 inch coastal guns. Group shot used as propaganda for the 15 inch coastal guns.

Stanley is the man circled in red.

Pat, who was of Dutch heritage, grew up in Singapore together with her two younger brothers, Kenneth and Duncan. Her parents were immensely protective over their only daughter which gave Stanley a large obstacle to overcome, while he was trying to court the young lady. Stanley managed to get permission from her parents to court her, on the condition that they would always be chaperoned by a family member.

With the invasion of the Japanese Army imminent, Stanley's primary concern was for the safety of Pat. He raised this concern of his with her family and explained that should they allow Pat to marry him, he would have her evacuated with all the other married families back to England and to his mother's home in London. After much persuasion, Stanley successfully convinced her parents on allowing the marriage. The couple were wed in a Registry Office or Army Chapel on 20th December 1941. Stanley was 21 years of age and Pat was 16 and a half.

Leo Rawling's portraits of Pat Bracken & Stanley Durston Leo Rawling's portraits of Pat Bracken & Stanley Durston

Although Pat was supposed to be evacuated, she refused to leave the country, wanting to be by her husband's side. She stayed with Stanley in a small rented room in the married quarters. However, Stanley was soon ordered to return back to the barracks as war was becoming imminent. This meant that Pat (who was pregnant) had to return to her parents' home in Katong.

When Singapore eventually fell, Stanley's officer in-charge instructed him to quickly return to his wife. This was because it was rumoured that the Japanese were going around raping and mercilessly killing civilians. Just as Stanley returned to Katong to pacify his very distressed wife, a Japanese sergeant barged in. Stanley was able to convince the Japanese sergeant that Pat was his wife, and with that the sergeant turned on his heels and left the couple and Pat's family unharmed.

However, the same Japanese sergeant along with two other Japanese soldiers, subsequently returned and arrested Stanley and had him sent to a POW camp. While interned, Stanley found means and ways to sneak out and meet Pat, and even at one point, jumping off a truck that happened to be passing by her place of residency.

On Pat's side, many of her relations had tried to flee but failed at doing so. Many of them either drowned or got lost at sea while trying to flee from Singapore Harbour. She continued to live in Singapore with her parents and brothers as a civilian however they were forced to wear a 'red star' on their shirts. Then, all 'enemy aliens' (family members of those in the Singapore Volunteer Force and British Army) were forced to wear these 'red stars' to indicate that they were an enemy alien.

Example of a 'red star' worn by Japanese 'enemy aliens'.

Donated by Christopher and Felicity Stonehill.

Worn by I.G Salmond.

In 1943, several Catholic and Protestant groups were sent up to Bahau, Pahang, to grow food for themselves, with little farming skills and/or tools. Pat's family was amongst those who were sent up there, and unfortunately, some of her family members never made it back to Singapore. Up in Bahau, she had lost both parents and a brother due to the terrible living and working conditions.

Stanley had survived life as a prisoner-of-war under the Japanese because of his resourcefulness and ingenuity. He managed to talk his way out of being sent to Burma to work on the railway which could have possibly saved his life. For survival, he would buy and sell smuggled cigars and food. He would also send whatever money he earned to Pat and his baby daughter Barbara, whenever he could.

At the end of the war in 1945, he was finally reunited with his wife and daughter. They subsequently moved to Liverpool, Britain, a week after liberation and reunited with Stanley's mother. They continued to live in Britain until 1958, when they decided to move to Australia and continue raising a family there.

Pat died of pancreatic cancer in 1982 at the age of 57. Stanley died of bowel cancer, a day before what would have been Pat's birthday, in 2001. They peacefully passed away, leaving behind their 5 children, 14 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

An adaptation of 'Survival and Across The Boundaries of Time' by Carol Payne, daughter of Stanley and Pat Durston. Donated to the museum in 2005.

________________________________________________________________

|

|

Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942.

Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942.

One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix.

One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix.