Thursday, February 1, 2007

Many stories have been born out of those dark days of Singapore's history that was the Japanese Occupation. Death and torture was everywhere, and it became a struggle for the men and women of those times merely to survive, to keep on a gentle string what little of their lives they still had left.

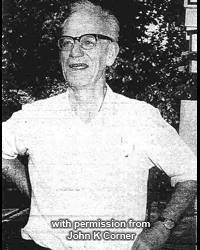

A fine example would be that of Professor Edred John Henry (E.J.H) Corner (1906 - 1996), who was not a military-man, but, in fact, a botanist. In sepia-tinged photographs, he is exactly what you would expect him to be: bespectacled, mild-looking and keen-eyed. Pictures of him with family leave it difficult to imagine that their lives were under the strain of such a cruel war.

Corner was born in London in 1906. His interest in Botany began at Rugby School and developed strongly at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. This was before he was appointed as the Assistant Director of the Gardens Department of the Straits Settlements. in 1929. Corner was an expert who who achieved many academic medals and scientific recognition including the Darwin Medal in 1960. He also became well-known for his skill of using Berok monkeys to help him obtain plant specimens that were too high in the canopy to collect. He remained a prominent figure in his field, until the arrival of the Japanese in 1942.

Corner was drafted as a member of the Singapore Volunteer Force. However, he was unable to fight after receiving a serious bite from one of his monkeys.

On the verge of Singapore's fall to the Japanese, the British Governor of Singapore, Sir Shenton Thomas, scribbled a note addressed to the new Japanese commander, recommending that Corner along with Professor Eric Holttum (director of the Botanical Gardens) and William Birtwhistle (Director of Fisheries) should be allowed to continue their work in the gardens to preserve the island's plant-life. Birtwhistle was conversant in the Japanese language after visiting Japan several years before Singapore's fall. Being familiar with the Japanese culture, he was well-respected by the Japanese. It was due to this that he was selected by Sir Shenton Thomas to preserve the Botanical Gardens along with Corner and Holttum.

The Japanese Emperor Hirohito, being an orchid enthusiast himself, gave direct orders to allow these men to continue their work with the Japanese. Also, Corner strongly believed that when it came to Science, any prejudice against any scientist of a different nationality or race, was unjustified. He believed that scientists had to be judged for their scientific work and research. Hence, upon the fall of Singapore, the men followed orders and continued their scientific work in the Botanical Gardens and were labelled as 'enemy aliens' by the Japanese and like other 'enemy aliens' they were required to wear a red star.

John Corner and William Birtwhistle, seen here, each wearing a patch with the red star on their shirts. The red star was worn by enemies of the Japanese who

were allowed to live outside prisons or camps.

With the assistance of Professor Hidezo Tanakadate and Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa, the men had successfully protected thousands of scientific specimens and hundreds of collections from the museums and libraries during a time chaotic with looting and destruction. Their close working relationship with the Japanese however, resulted in many calling them a collaborator with the enemy. This was despite the fact that Corner himself had even organised food rations and supplies during the trying time of the Japanese Occupation. Many did not know that Corner had been smuggling food into prison camps for them.

The three men were however commended in the November 1945 General Report to the British Colonial Office -

Reference No: CO 273/675/6

His controversial image continued after the end of the war and long after he had left Singapore in November 1945. Following his departure, he became Principal Field Scientific Officer for Latin America for UNESCO from 1947 to 1948, before returning to Cambridge and becoming Professor of Tropical Botany. He continued to lecture at Cambridge until 1973, when he retired as Emeritus Professor.

In 1981, Professor Corner charted his wartime experiences in the book, 'The Marquis: a tale of Syonan-to’. In this book, he mentioned a note from Sir Shenton Thomas, that had given him approval to help preserve the Botanic Gardens and Raffles Museum. According to him, this note was lost in a fire in 1945 in Sendai, Japan, however, which only kept matters ambiguous. The book was shied away from by British publishers, and was only published by Heinemann (Asia). Professor Corner’s other works include several scientific books and papers, as well as a scientific obituary of the Emperor Hirohito written for the Royal Society.

It was only in 2000 that evidence was found that the destroyed note had been published in a Japanese newspaper in 1942, the Asahi Shimbun by Professor Tanakadate.

Corner was a man of high principle who devoted his life to Botany. In his writings he changed the face of much that had gone before and the evidence now is overwhelming that he never collaborated with the Japanese but rather he gave sufficient co-operation to ensure the safety of all the vital scientific records. As an enemy alien he was also able to help many prisoners, but entirely anonymously and at great risk to himself. He was a self-effacing man who shunned that kind of recognition. His scientific work was everything to him.

John Corner at the age of 66. Photograph taken by Ismail bin Ahmad.

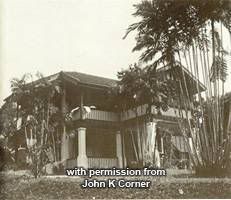

To date, opinions of Professor Corner remain divided. Some maintain their distrustful image of him despite evidence of his innocence, while others, notably students, remember him fondly for his teaching and the stories he had to tell and they see him as a hero who held his own and was true to himself. Corner's colonial bungalow on Cluny Road, now within the Singapore Botanical Gardens, has been converted into a restaurant and is fondly remembered as the "E.J.H Corner House".

John Corner's colonial bungalow house at 30 Cluny Road.

Now a restaurant in the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

Professor Corner had unfortunately passed away before he got this chance to clear his name. He died in 1996 at the age of 90. He married twice in his lifetime, and is succeeded today by a son and daughter.

The museum extends their appreciation to his son, John Kavanagh Corner for sharing the story of his father, Professor Corner, and donating articles and photographs of him to the museum. The family photograph above was taken in 2003. From left: John K Corner's children, Andrew Corner and Katie Buckley, Corner's wife, Belinda, John K Corner and Belinda's cousin.

John K Corner can be contacted at astley22@bigpond.net.au for further information and the full 1945 General Report. Drafted by volunteer writer Lyana Shah.

________________________________________________________________

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home