Sunday, April 1, 2007

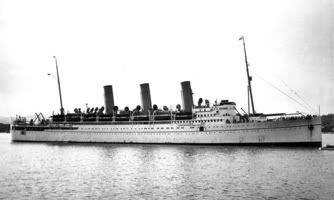

As war began to break-out in the Pacific Region, Fred, along with thousands of other men, volunteered to serve in the British Merchant Navy and was set onboard the Empress of Asia. Built in Glasgow in 1912, the 180 meters long ship weighed 17,000 tonnes and was a passenger liner. But with war raging, the Empress of Asia was converted into an armed troop carrier crewed by the civilian Merchant Navy seamen. Fred Bailey with his wife, May By late 1941, The Empress of Asia was sailing for Singapore via Africa, Bombay and across the Indian Ocean, but never made it to the island. On 3rd February 1942, when the cruiser was just 13 miles away from Singapore, it was attacked by the Japanese. The vessel was heavily bombed and subsequently sunk. The crew (Fred Bailey among them) and the ship's military passengers, managed to escape the burning vessel and were eventually rescued by small dinghies or vessels passing by and they were subsequently brought to Singapore. As the men came ashore, they were shocked to see the state of Singapore at the time. "I was driven through Singapore which was a devastation. In the hospital, the dead were mixed up with the living. The wounded weren't treated or fed. There was nobody to cook for them." Leonard Butler In response to the appalling conditions, 147 'Empress' men, including Fred, turned down the offer of a passage home and volunteered to tend to the sick and wounded. Even at the point when the Japanese had taken over Singapore city, Fred and his fellows were still helping to tend to the injured at the Singapore General Hospital. Since the British Merchant Navy crew members were not classifed as military personnel, and not in uniform (unlike Royal Navy sailors), the 'Empress' crewmen were taken as civilian prisoners by the Japanese. Fred was subsequently imprisoned in Changi Gaol as one of the 3,500 civilians, held in a place built to hold only 600 people. During his internment in the prison, Fred had to share a cell with his fellow crew members, Harry Arnold Hesp and William Hughes. The cell that was designed for one prisoner, was to be the Fred's home for the coming years which he had to share with his two new cellmates. Conditions in the prison were harsh because of overcrowding, lack of food, the outbreak of diseases and the brutality of the Japanese sentries. However, Fred never lost his impish sense of humour and after the war, many of his fellow prisoners testified that his capacity for finding laughter even at the bleakest situations played an important role in maintaining spirits and in giving teh captives the strength to endure. Through documents donated to the museum by Fred's nephew, Michael Beddard, Fred was evidently likeable character amongst the other inmates, helping to keep spirits high. Fred intended to give this cross to his wife, May, as soon as he returned to Britain. However, on the voyage home, he learned that May had passed away from an asthma attack after learning that her husband was safe and returning from Singapore after more than three years of worrying about his fate. Hence upon his return, he was not only burdened with the loss of his wife but was also burdened with the challenge of rekindling his relationship with his two daughters who barely recognised their own father. May's mother, Emily Vernon extended her support to her son-in-law by helping to raise his daughters, Freda and Sheila. In appreciation for her actions, Fred gave the cross to her. Back at home, Fred was still a popular local character in his small town, selling eggs from a basket on his bicycle. The humour and cheer that he carried with him never dwindled, even when he had lost both his legs (as a result of harsh punishments he was compelled to endure whilst in Changi). Reverend Bishop Wilson (above) Fred Bailey passed away at the age of 78, in 1987. The crucifix (left) that was given to Emily Vernon, was kept safely as one of her most treasured possessions. It was eventually passed down to her grandson Michael Beddard, before she died at the age of 94. The crucifix was donated to the museum in 2005 by Beddard himself and currently resides and is on display at the Changi Museum. "I may never know for sure what the design means but I know what the cross symbolises for me - that the outward differences between people don't really matter: an ordinary working man like Fred and a Prince of the Church like the Bishop, can find themselves in the same circumstances and become friends." Michael Beddard, nephew of Fred Bailey The museum extends its appreciation to Michael & Pam Beddard, Freda Alcock and Sheila Hewitt for their kind donations and accounting their uncle's/father's history to be preserved in the museum and remembered by the generations to come.  Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942.

Born in 1902, Frederick Charles Bailey had lived a simple and humble life, rarely exploring beyond his home-town in Northwich, Cheshire (north-west England). He lived comfortably with his wife and two daughters, earning a living by selling fruit and vegetables from a horse-cart. Little did he know that the simplicity of his life was to change by 1942.

The Empress of Asia

(image is property of the Empress of Asia Research Group)

Empress of Asia's youngest survivor

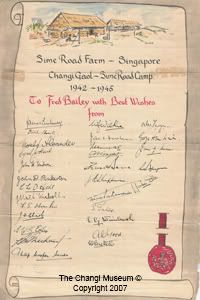

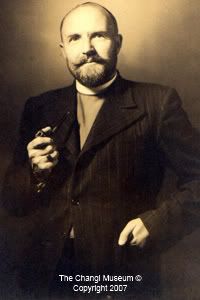

A drawing of scroll and Sime Road Camp with the signatures of several other captives of varying professions. Given to Fred Bailey during his interment. The document serves as evidence of the impact his personality had on his fellow inmates. One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix.

One such inmate was the Rt Rev Leslie Wilson, Bishop of Singapore. At the end of the war, Rev Wilson had given Fred Bailey a parting gift - a simple crucifix.

________________________________________________________________