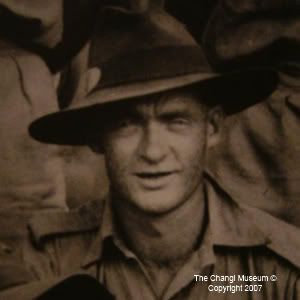

Serving for the 2/30th Australian Infantry Battalion in Singapore, Private George Aspinall (right) (1923 - 1991) had shown great tenacity, ingenuity and resourcefulness as a Prisoner of War (POW) during the Second World War. George did not meet the minimum age requirement to join the Army so he had used his cousin's birth certificate instead to enlist into the Army. The Australian left for Singapore at the age of 18 in 1941. Before he left, his uncle had given him a Kodak 2 camera as a going-away gift which eventually became a vital tool used by George to record his experiences in Singapore, Malaya and Thailand during the Second World War.

By 1942, the Allied powers had lost the Battle for Singapore to the Japanese and George Aspinall, along with thousands of other men, became a Prisoner-Of-War for the Japanese. At the point of time, Selarang Camp (in Changi) was the main POW camp to house the Australians.

George began to run out of film not long after he arrived in Changi, but while he was working on the Singapore docks he stumbled upon some X-Ray equipment. He found boxes of negative film, developer and other chemicals. George had applied what little he had learnt about developing photographs [from a Chinese photographer] and learnt to use the X-Ray equipment to process whatever photographs he took.

He experimented with the X-Ray film, developer and fixer and even worked out a way of cutting the X-Ray film to fit his camera. However, this meant that he could only take one photograph at a time because he had to reload fresh X-Ray film after every shot. He would usually load his camera at night and take photographs in the day.

George documented his life as a Prisoner of War with the photographs he took; at times risking his life to take photographs. He did this during his internment at Changi and even up at the infamous Thai-Burma railway where he worked as a slave labourer. He continued until he 1943. Before returning back to Singapore from Thailand, the Japanese military police (Kempetai) were conducting very thorough searches. Afraid that he would get caught, George broke his Kodak 2 camera and threw it down a deep well. However he did continue to hide the processed negatives in a canister down a toilet borehole in the grounds of Changi Gaol.

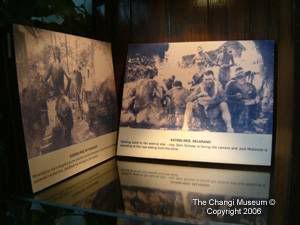

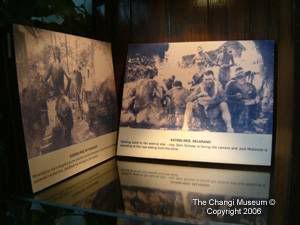

In later years, George's photographs became a vital source of information in portraying and accounting the atrocities of the Second World War and was even used as pictorial evidence at the Rabaul War Crimes (1946). His persistence in taking photographs despite the risk of getting caught, was not entirely stemmed by a need to document the brutalities of war. Instead, he was merely taking photographs for the purpose of illustrating to his own family, life for him as a young soldier in Singapore and subsequently as a POW for the Japanese. His story and photographs were compiled into a book by Tim Bowden, entitled 'The Changi Photographer'.

The Changi Photographer: George Aspinall's Record of Capitvity

by Tim Bowden